Hit the Books with Dan Milnor: Embracing Local Photography

In 1996, I was working as a freelance photographer, and although I had been working full-time for several years, I was still very much at the beginning of my career. My vision of being a professional photographer (a photojournalist to be specific) wasn’t quite matching the reality of my life, but I was still holding out hope—hope that I would someday be the globetrotting photojournalist covering the exotic stories. I had been lured to photojournalism by the coverage of the Vietnam War, and in my mind, that was the kind of story I should be covering.

By this time, I had managed to go abroad. My photography portfolio contained stories from Cambodia and Guatemala and a few other far-flung locales, but it felt like I needed more. I also felt that where I was living, Phoenix, was a city that could never lead me to the photojournalism promised land.

Around this same time, I got the rare chance to show my portfolio to the photo editor of what I considered to be the dream magazine. This was the same magazine that all my peers wanted to work for, a publication that signified the best of the best when it came to long-form documentary photography. It was just him and me. He wore a suit and tie.

He slowly flipped through the pages of my portfolio. “Where are the local stories?” he asked. I had done local stories, but only when assigned, and I hadn’t seen these stories as something that would be of interest to a high-level photography editor. “Just about anyone can go to an exotic location and make pictures,” he said. “But telling stories locally is where I can see how talented you really are.”

My photography from the exotic locations didn’t make a dent on this man because not only had he seen it before, but he had also seen it done far better. He was responsible for a staff of dozens of the best documentary photographers in the world who specialized in telling stories from the far reaches of the globe. What the photo editor was attempting to illustrate to me was that working locally was not only the best way to find easily accessible stories (stories that didn’t require massive budgets and international airfare) but also the best way to find stories that would allow enough time for me to make real connections in my own community. Great photo essays require depth and often the only way to achieve this depth is through copious time and access. I left our meeting with new eyes regarding the community outside my front door.

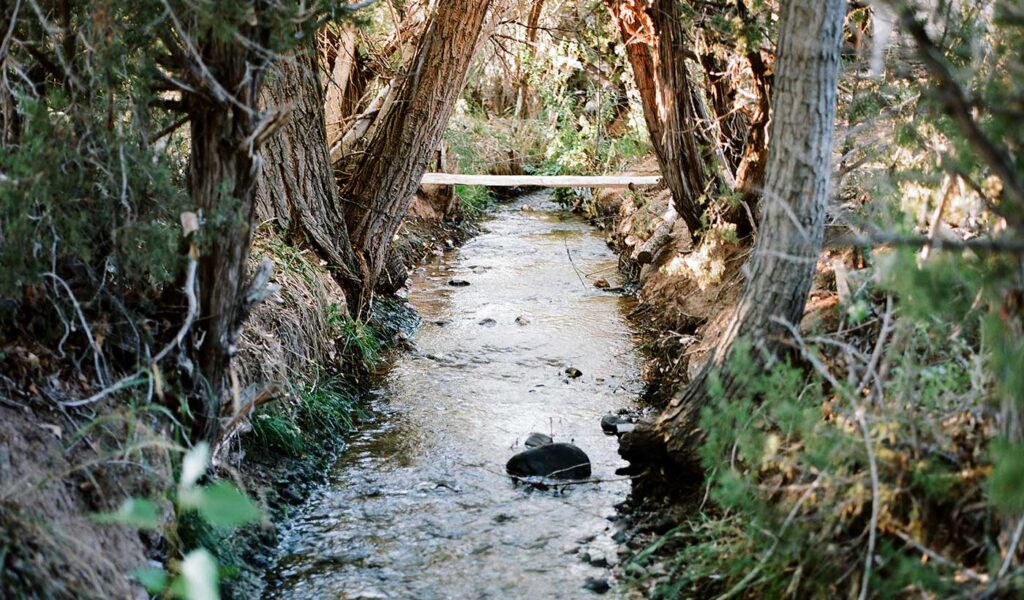

I emerged into the Arizona desert with renewed focus and tenacity. I started a story on people who had dropped out of society and were living in remote camps in the wild. I started another project on the farm and ranch land being usurped by the rapid expansion of the city of Phoenix. And I also began working on the border.

What began to emerge in my photography was a sense of community. Not only did I feel like I had a better understanding of my state, but I also began to feel like I was a small part of something larger and my role and responsibility was that of visual historian. My job was simply to record for the now and for the when of an unknown future. I realized that global stories could be told from a hyper-local angle. Most international stories, things like climate change, immigration, conflict, energy, or global health could be explained and illustrated by a single human being living in the American Southwest. Was a water issue in Arizona that different from a water issue elsewhere? Now I live in New Mexico, and when asked where my favorite place to photograph is, my response is immediate: “Here, where I live.”

Ready to publish your book? Check out our professional services to get started!